The Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) is poised to create a sea change in how corporates identify, assess, and report on their sustainability-related risks and opportunities. The founding principle of the CSRD, that of double materiality, will significantly expand companies’ disclosure and reporting requirements. This means that every one of the ~50,000 in-scope companies will need to undertake a double-materiality assessment to determine which sustainability issues are most significant to organizations and their stakeholders.

However, beyond the CSRD, the concept of “materiality” remains elusive to many. To bridge this gap, this blog post will first provide a general primer on materiality before unpacking what double materiality entails within the context of this watershed regulation.

Materiality—from the 10,000-foot level

The term materiality essentially means ‘significance’ or ‘importance’ and has roots in financial accounting. According to Harvard Business School, materiality pertains to the importance of information within a company’s financial records.

Likewise, in the sphere of corporate sustainability, ESG issues or concerns that are deemed significant are regarded as material. However, what is material to a particular organization varies based on the exact nature of its business activities, its location, and where it operates.

Issues identified as material are significant because:

- Stakeholders care about them and make decisions based on how the company manages them;

- Operating and financial performance are affected by how well the company manages them (think revenues, operational costs, expenses, R&D investments, etc.);

- Society and the environment are affected by how well the company manages them;

- The legal status of the company can be harmed through exposure to compliance risks, litigation, reputational damage, and shareholder activism.

Notably, the concepts of materiality and decision-usefulness are intimately connected. In the ESG reporting context, “decision-useful” pertains to the quality, clarity, and relevance of the reported information, to facilitate the intended users’ ability to make informed decisions. The World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) underscores this point well:

“Generally, the concept of materiality is intended to generate information that is useful for decision-making both by reporting companies and the intended audience.”

Indeed, the proper management of ESG business risks and opportunities informs the decisions key stakeholders make, decisions that can have direct—and profound—consequences on a company’s performance.

Financial and impact materiality: what’s the difference?

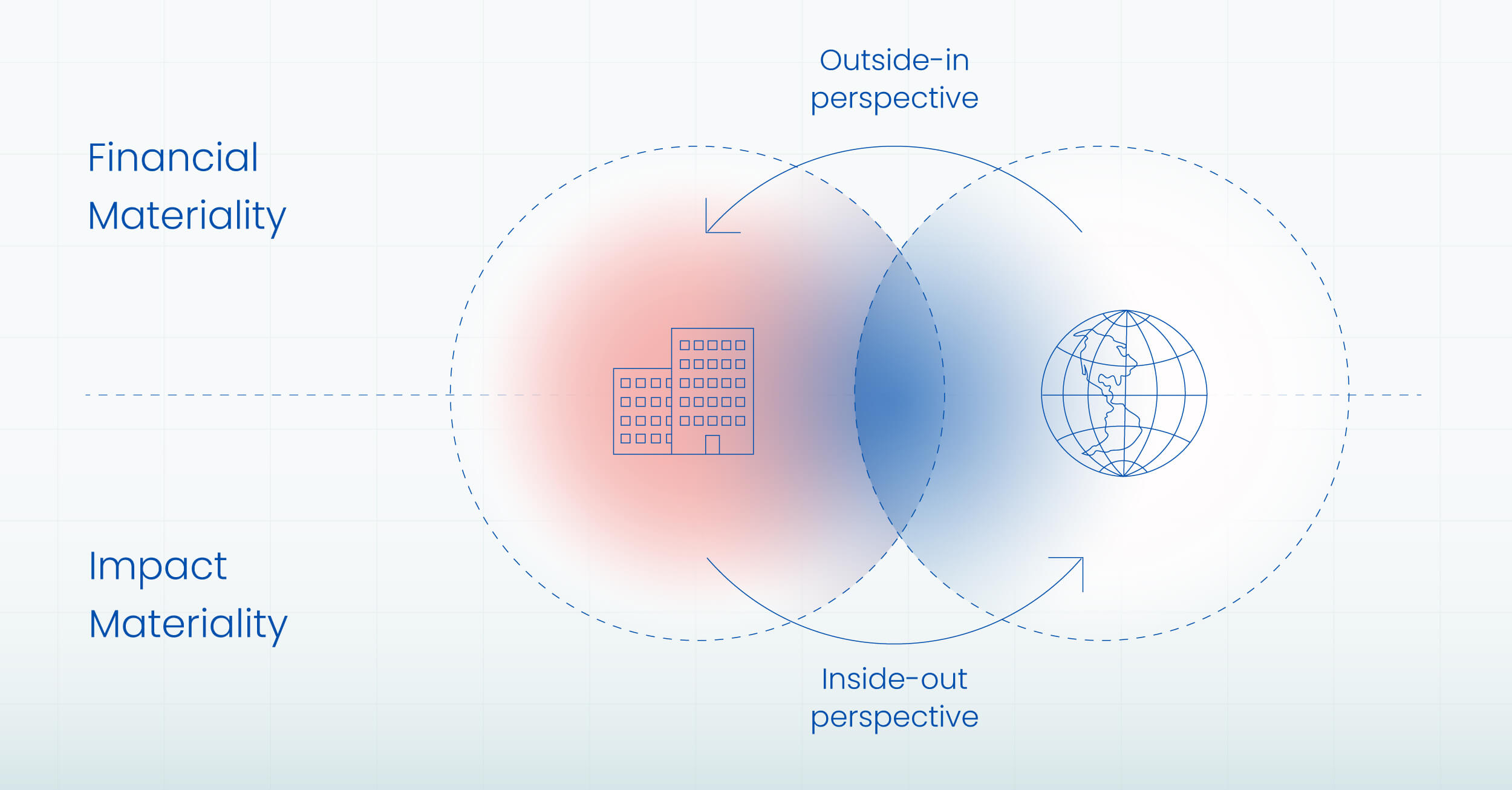

Understanding the difference between financial and impact materiality—essentially, the two sides of double materiality—entails grasping the distinction between ESG and sustainability. While ESG and sustainability are inextricably linked, they are not the same. Often referred to as the “micro” vs. “macro” perspectives respectively, financial and impact materiality can be differentiated as follows:

- Financial materiality pertains to how ESG issues affect the company’s operations, financial performance, risk profile, etc. In a broad sense, this perspective helps ascertain how the company’s value is affected. Financial materiality is typically of concern to investors.

- Impact materiality reflects the company’s external impacts (both positive and negative) on people, the planet, and society. This perspective is typically of most interest to citizens, consumers, employees, business partners, communities, and civil society organizations.

Another way to understand impact materiality is by ascertaining how a company’s business activities affect the ecosystems in which they’re embedded—this is also referred to as an “inside-out” perspective.

- For example, a clothing manufacturer located near a river releases harmful chemicals into a waterway, affecting the local ecosystem and communities downstream. Consequently, the company will need to disclose information about its discharge of pollutants, actions taken to minimize its environmental harm, and strategies for remediation. This transparency is crucial for stakeholders concerned about the environmental consequences of the company’s activities.

In contrast, financial materiality entails taking an“outside-in”view. This is about how sustainability-related developments and events affect organizations, creating both risks and opportunities.

- For example, consider a large firm in the automotive industry that has been dealing with public concerns regarding the safety and effectiveness of a line of cars; over the past few years, the company has faced numerous legal actions and regulatory inquiries. Hence, it becomes crucial for the company to disclose information concerning its safety procedures, quality assurance methods, and legal obligations linked with recalls or unfavorable incidents. Such disclosures hold significance for investors examining the company’s financial health and risk management strategies.

Ultimately, failing to prioritize materiality exposes a company to risks like operational inefficiencies, accusations of greenwashing, and financial penalties, potentially tarnishing its reputation and impeding long-term success.

Double materiality in the context of the CSRD

To report under the CSRD’s European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS), companies will be required to disclose sustainability information based on the “double materiality” principle. In simpler terms: the principle of double materiality will help companies decide which sustainability issues to disclose, mandating them to think about sustainability in two ways (i.e., both impact and financial materiality).

The ESRS’ double materiality perspective requires companies to conduct a due diligence assessment to determine their material dependencies and impacts on the environment and people (i.e., impact materiality), as well as the material risks and opportunities to their operations and financial performance (i.e., financial materiality). Therefore, companies will only need to disclose on the standards’ topics, disclosure requirements, and data points that are material, or significant to them.

Two notable exceptions are:

1) Climate change;

2) The Principle Adverse Impact (PAI) indicators prescribed by the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR); companies that do not consider either of these to be material must explain why.

When determining impact materiality, it’s important to note that companies will need to look beyond their own operations: they’ll need to determine their impacts across their entire value chain. Thus, any negative impact within the value chain, regardless of whether the company directly executed the action or not, could potentially be identified as a material concern.

While companies might be more used to adopting a financial materiality approach (geared towards investors’ information needs), the CSRD mandates a renewed emphasis on understanding and managing a company’s impacts on the ecosystems in which operates. In turn, the aim is to provide a more balanced or two-sided perspective and to avoid ‘one-sided reporting’ that prioritizes investors’ information needs at the expense of how the company is generating value for society.

A closer look at the ESRS

Developed by the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG), the ESRS will require that companies disclose material sustainability-related information as part of their management report, for the same period as financial information. Essentially, this will place sustainability disclosures in general regulatory filings.

The volume and granularity of the sustainability information to disclose is unprecedented in scope. In total, the ESRS encompasses 1,144 data points, a mixture of both quantitative and qualitative information. And, while only the General Disclosures in ESRS 2 will be mandatory for all in-scope companies, all the other standards are subject to a materiality assessment—which is also subject to “external assurance in accordance with the provisions of the Accounting Directive.”

Perhaps one of the most daunting aspects of the CSRD is the sheer cost of undertaking the double materiality requirement, with EFRAG distinguishing between indirect and direct costs. For the latter, EFRAG’s estimates amount to “about EUR 320 000 per year for an average NFRD listed undertakings after all requirements have been phased in.” As expected, costs will vary depending on the characteristics of the preparer (size, complexity, etc.) with “NFRD listed undertakings” anticipated to incur the largest preparation costs for their sustainability statements.

Double materiality—in action

To illustrate the practical implications of double materiality, we’ll examine three real-world scenarios across three different industries (agricultural, extractives, and pharmaceuticals). Each one addresses a unique ESG issue, namely: biodiversity loss, geopolitical instability, and product safety. It’s important to note that not all ESG issues will be amenable to a double materiality assessment.

Biodiversity loss and the agricultural industry

Financial materiality: Many agricultural businesses rely on pollinators to ensure successful crop yields. These vital creatures play a pivotal role in the production of fruits, vegetables, nuts, and seeds—foundational to various food supply chains. However, the decline of pollinator populations (due to biodiversity loss) can have significant consequences: reduced crop yields and increased production costs for farmers. In turn, this can directly affect the economic viability of agribusinesses.

Impact materiality: The impact of biodiversity loss has the potential to disrupt ecosystem processes, weaken resistance to pests and diseases, and impair soil vitality. Furthermore, it jeopardizes the livelihoods of small-scale farmers and communities reliant on agriculture for sustenance.

Geopolitical instability and the extractive industries

Financial materiality: Instability on the geopolitical front can have negative repercussions on the financial performance of companies in the extractive industries. Civil unrest, regulatory shifts, and conflicts have the potential to interrupt business operations, resulting in heightened expenses, disruptions in the supply chain, or even the loss of assets through expropriation. Thus, to maintain financial stability and their long-term viability, companies must evaluate and mitigate such risks.

Impact materiality: Geopolitical instability also has significant non-financial consequences. For instance, extractive companies are frequently under scrutiny for their environmental footprint, human rights practices, and impact on local community development. Geopolitical instability can exacerbate these issues, leading to conflicts over land usage, increased pollution/emissions, and human rights violations.

Drug safety and the pharmaceutical industry

Financial materiality: Incidents related to product safety, like adverse drug reactions, recalls, or litigation, can have significant financial implications for pharmaceutical companies. These can include the costs of regulatory penalties, legal resolutions, reputational damage, and market share declines.

Impact materiality: Taking steps to ensure drug safety and efficacy is a core ethical responsibility. This ensures the protection of public health, upholds patient rights, and sustains trust in their brands and the pharmaceutical industry as a whole.

Beneficial or burdensome? The CSRD’s double materiality assessment

Unlike the U.S. SEC’s Climate Proposal and the International Sustainability Standards Board’s (ISSB) focus on single materiality (i.e., financial materiality)—and the GRI Standards’ impact materiality focus—the CSRD’s expanded scope is anticipated to create new challenges for reporting companies.

Potential challenges

- Not one, but two. Companies that have historically focused on financial materiality will now have to go the extra mile to also determine their impact materiality, which will require more time and resources to execute well. This will become even more arduous in the absence of a robust data governance structure.

- A whole-of-value-chain approach. Companies will need to assess their material impacts and dependencies—along with their associated risks and opportunities—not only for their own operations but also for their direct and indirect business relationships in their upstream (e.g., suppliers) and downstream (e.g., customers) value chain. This could be especially challenging for companies with extensive value chains.

- Selecting the right stakeholders. Selecting the ‘right’ stakeholders can be tricky, particularly for impact materiality. Beyond the fact that the concept of ‘impact’ is subject to interpretation, selecting the appropriate stakeholders may vary significantly depending on the specific sustainability issue in question.

- Conducting a one-size-fits-all assessment. Oversimplification of the materiality assessment should be avoided at all costs. Yet, it can occur should companies fail to recognize that materiality is determined by context, which may vary within the scope of its operations from one location to another, or from one business unit to another. Such variations originate from three main sources, namely: geographic location, nature of operations, and jurisdiction.

Naturally, these challenges will be compounded should companies lack the necessary infrastructure, systems, and data management capabilities to handle their sustainability data and reporting effectively.

Nonetheless, new value can be created…

Perhaps the perception of the CSRD’s double materiality assessment as unduly complex and burdensome can be assuaged by seeing the glass as half full—even for just a moment. At the very least, it might appear less daunting if we consider its benefits and value-creating properties. But, what are they?

Double materiality can be a source of value creation, by:

- Examining the entire value chain over the short-, medium-, and long-term horizons;

- Supporting the selection of only the most pertinent information for users of the report (i.e., company-specific);

- Helping identify, and engage with, the stakeholders most affected by the company’s impacts;

- Clearly mapping, prioritizing, and evaluating the organization’s sustainability-related impacts, risks, and opportunities, and thereby

- Creating an opportunity to truly embed sustainability into their business model and strategy.

Ultimately, conducting a materiality assessment is a proactive exercise, one that is heavily focused on risk mitigation and risk management. It can also highlight where a company’s core data gaps are, and where it has room to grow and improve.

Importantly, having an effective governance framework in place will help manage the insights derived from the assessment. Remember: core business strategies cannot be adapted in the face of sustainability information voids and unruly data management.

What now?

The CSRD was created to bring sustainability reporting on par with traditional financial reporting. Given its unparalleled rigor, grounded in the double materiality principle, it’s set to do just that.

If you’re one of the ~50,000 companies to fall under the CSRD’s scope, conducting a double materiality assessment to pinpoint your ESRS impacts, risks, and opportunities is highly recommended. However, a key question remains: how is this meant to be done?

Get the answers you need in our white paper “Seizing the CSRD Opportunity” where we provide in-depth information about the CSRD double materiality assessment—including common pitfalls—plus practical recommendations to get started on the right foot.

Download the white paper today.